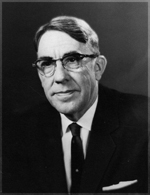

Professor Emeritus Arthur L. Samuel died July 29, 1990 at Stanford hospital from complications related to Parkinson's disease. Arthur Samuel was a pioneer of artificial intelligence research. His life spanned a broad personal and scientific history.

Arthur Samuel was born in Emporia, Kansas in 1901. He graduated from M.I.T. with a Master's of Science degree in Electrical Engineering in 1926, working intermittently at General Electric Co. in Schenectady. He later did graduate work in Physics at Columbia University. His undergraduate school, the College of Emporia, awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1946. After his master's degree he stayed on at M.I.T. as an instructor in Electrical Engineering until 1928, when he joined Bell Telephone Laboratories. At Bell Labs he mainly worked on electron tubes. Particularly notable was his work on space charge between parallel electrodes and his wartime work on TR-boxes. This is a switch that disconnects the receiver of a radar when the radar is transmitting and prevents the sensitive receiver from being destroyed by the high power transmitter. In 1946 Samuel became Professor of Electrical Engineering at the University of Illinois and became active in their project to design one of the first electronic computers. It was there he conceived the idea of a checker program that would beat the world champion and demonstrate the power of electronic computers. Apparently the program was not finished while he was at the University of Illinois, perhaps because the computer wasn't finished in time.

In 1949 Samuel joined IBM's Poughkeepsie Laboratory. This move was seen by IBM's competitors as a commitment by IBM to vacuum-tube based computing, but as his autobiography describes it, he had to fulfill a dual role there: pushing research on switching transistors and keeping engineers going with the available tube technology. Tubes were used for logic and memory in IBM's first stored program computer, the 701. The memory was based on Williams tubes which stored bits as charged spots on the screen of a cathode ray tube. Samuel managed to increase the number of bits stored from the customary 512 to 2048 and to raise the mean time to failure to half an hour. Memory capacities of those machines eventually grew to 8K words. He completed the first checker program on the 701, and when it was about to be demonstrated, Thomas J. Watson Sr., the founder and President of IBM, remarked that the demonstration would raise the price of IBM stock 15 points. It did. The Samuel Checkers-playing Program appears to be the world's first self-learning program, and as such a very early demonstration of a fundamental concept of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Programs for playing games fill the role in AI research that the fruit fly (Drosophila) plays in genetics. Drosophilae are convenient for genetics because they breed fast and are cheap to keep, and games are convenient for AI because it is easy to compare computer performance with that of people.

Samuel took advantage of another fact about checkers for his learning research. Namely, the checker players have access to many volumes of annotated games with the good moves distinguished from the bad ones. Samuel's learning program replayed the games presented in Lee’s Guide to Checkers to adjust its criteria for choosing moves so that the program would choose those thought good by checker experts as often as possible. In 1961, when Ed Feigenbaum and Julian Feldman were putting together the first AI anthology, Computers and Thought, they asked Samuel to give them, as an appendix to his splendid paper on his checker player, the best game the program had ever played. Samuel used that request as an opportunity to challenge the Connecticut state checker champion, the number four ranked player in the nation. Samuel's program won. The champion provided annotation and commentary to the game when it was included in the volume.

Because his checker work was one of the earliest examples of non-numerical computation, Samuel greatly influenced the instruction set of early IBM computers. The logical instructions of these computers were put in at his instigation and were quickly adopted by all computer designers, because they are useful for most non-numerical computation.

Samuel was a modest man, and the importance of his work was widely recognized only after his retirement from IBM in 1966. He did not relish the politics that would have been required to get his research more vigorously followed up. He was also realistic about the large difference between what had been accomplished in understanding intellectual mechanisms and what will be required to reach human level intelligence. Samuel's papers on machine learning are still worth studying. With great creativity and working essentially alone, doing his own programming, he invented several seminal techniques in rote learning and generalization learning, using such underlying techniques as mutable evaluation functions, hill climbing, and signature tables. One still hears proposals for research in this area less sophisticated than his work of the 1950s.

Besides engineering and computer science, Samuel did important management work at IBM. He played a large role in establishing IBM's European laboratories and setting their research directions, especially in Zurich. This laboratory did important work in physics, leading to several Nobel prizes. He became the editor of the influential IBM Journal of Research and Development.

Samuel retired from IBM in 1966 and came to Stanford University as a Lecturer and Research Associate, starting yet another second life. In 1974 he became a research professor here. He continued his work on checkers until his program was outclassed in the 1970s. He also worked on speech recognition until the funding agency, DARPA, decided to concentrate its speech work on developing one single approach. Arthur was actively teaching up to 1982. Arthur Samuel remained an active computer programmer long after age forced him to give up active research. His contributions included work on the SAIL operating system, on Software for the Livermore S-1 Multi-processor, and on the TEX typesetting system. His last work, continued up to the age of 86, involved modifying programs for printing in multiple type fonts on some of the Stanford Computer Science Department's computers. We believe he was the world's oldest active computer programmer. The Stanford computer he used tells us that he last logged into it on February 2, 1990.

One of Samuel's talents was understanding inadequate documentation of complicated programs and writing clear and attractive manuals. His `First Grade Tex' was recently translated into Japanese. Recently he started an autobiography, which, unfortunately, takes us only to the middle sixties. Arthur Samuel was a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the American Physical Society, the Institute of Radio Engineers, the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, and a member of the Association for Computing Machinery and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

As a person, Samuel was distinguished by his objectivity and his kindness in helping many people, especially in learning about the many matters in which he was expert.

Gio Wiederhold

John McCarthy

Ed Feigenbaum